For the past several years I have been a pre-screener of documentaries features and shorts for the Social Impact Media Awards. SIMA is an online platform founded in 2012 by Daniela Kon, to curate, promote and distribute documentaries (https://simastudios.org).

What has stood out every year is the number and quality of documentaries made in Israel, produced with private and public funding. It is a thriving scene that deserves ample distribution and scholarly assessment. Below I discuss a number of excellent titles, made between 2021 and 2024. I have included some of them in the Senses of Cinema World Poll of 2023 and 2024.

I have organized them in five main categories, according to subject matter:

1. The Jewish experience in Europe in the 1940s: The Address on the Wall (2022), Budapest Diaries (2024), 999: The Forgotten Girls (2023) and The Partisan with the Leica Camera.

2. Autobiographical documentaries. Lives in the first-person: The Artist’s Daughter, Oil on Canvas (2022), Egypt, A Love Song (2022). Empty Handed (2021), How to Say Silence (2021), M/Other (2024) and We Used to Sing (2021).

3. Israel: Cultural history. People in Israeli context: The Bankers Trial / Mishpat Habankaim (2022, Israel), The Camera of Doctor Morris (2022), Private Death (2021) and Razzouk Tattoo / Yoresh Hakakuim (2022).

4. Israel: Contemporary history and politics. Israel in the Middle East: Closed Circuit (2022),

40 Steps / 40 Tzeadim (2022), Generation 1.5 (2022), Homeboys (2022), Mourning in Lod (2023) and #Schoolyard. An Untold Story (2021).

5. October 7, 2023. Chronology of a pogrom: We Will Dance Again (2024) and 06:30 (2024)

All these films are good examples of Ken Burns’ counterintuitive insight about documentary:

“To the general public, the word ‘documentary’ or ‘nonfiction film’ is a narrow band. And we think that the feature film is this huge magnificent spectrum. But if you really look at it, the feature film is governed by a formula and laws of plot that make it, I believe, the narrow band in the spectrum. And it’s the documentary, it’s the nonfiction film, that has so many glorious possibilities.” (Liz Stubbs, Documentary Filmmakers Speak, 2002).

I have arranged them chronologically, from newer to older, transcribing the reviews I wrote at the time I screened them for the SIMA Award. Each year has its own blog entry.

I have organized them in five main categories, according to subject matter:

1. The Jewish experience in Europe in the 1940s: The Address on the Wall (2022), Budapest Diaries (2024), 999: The Forgotten Girls (2023) and The Partisan with the Leica Camera.

2. Autobiographical documentaries. Lives in the first-person: The Artist’s Daughter, Oil on Canvas (2022), Egypt, A Love Song (2022). Empty Handed (2021), How to Say Silence (2021), M/Other (2024) and We Used to Sing (2021).

3. Israel: Cultural history. People in Israeli context: The Bankers Trial / Mishpat Habankaim (2022, Israel), The Camera of Doctor Morris (2022), Private Death (2021) and Razzouk Tattoo / Yoresh Hakakuim (2022).

4. Israel: Contemporary history and politics. Israel in the Middle East: Closed Circuit (2022),

40 Steps / 40 Tzeadim (2022), Generation 1.5 (2022), Homeboys (2022), Mourning in Lod (2023) and #Schoolyard. An Untold Story (2021).

5. October 7, 2023. Chronology of a pogrom: We Will Dance Again (2024) and 06:30 (2024)

All these films are good examples of Ken Burns’ counterintuitive insight about documentary:

“To the general public, the word ‘documentary’ or ‘nonfiction film’ is a narrow band. And we think that the feature film is this huge magnificent spectrum. But if you really look at it, the feature film is governed by a formula and laws of plot that make it, I believe, the narrow band in the spectrum. And it’s the documentary, it’s the nonfiction film, that has so many glorious possibilities.” (Liz Stubbs, Documentary Filmmakers Speak, 2002).

I have arranged them chronologically, from newer to older, transcribing the reviews I wrote at the time I screened them for the SIMA Award. Each year has its own blog entry.

2021

How to Say Silence (2021, Israel) Dir. Shir Newman. 68 min

A trove of archival materials – home movies, newsreels and other historical footage – is well used to illustrate the various interviews, with the minor glitch that twenty or so minutes into the film, the personal story is temporarily disconnected from the historical compilation. It’s an editing choice that expands the background at the expense of the love story.

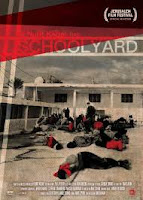

#Schoolyard. An Untold Story (2021, Israel) Dir. Nurit Kedar. 70 min

The short preface opening this documentary about the 1982 Israeli invasion of Lebanon to dislodge PLO forces describes “one of the first complications [that] occurred in the town of Sidon when a company of Israeli soldiers were given the task of guarding more than 1,00 detainees in a schoolyard”. Made with the support of public television, Schoolyard interviews a military officer, a medic, several soldiers, and doctors working in a Lebanese hospital, detained for several days, to reconstruct the “complication”. It led to the death of several detainees, killed by the soldiers in their attempt to keep their military orders.

Schoolyard is an excellent political documentary, pitched right, in tone and execution. A remarkable feat considering the nature of the project: the interviews, covering the whole spectrum, are restrained (à la Night and Fog), so that the facts sink more powerfully without editorial comment, contributing to the strong sense of humanity and sorrow. The reconstruction of those days via an effective montage of television news, photos from the Israeli archives and a present day visit to the schoolyard where this took place, is a lesson on how to combine oral history with an impactful audiovisual background. The film ends with photos of the dead Lebanese, an editorial strategy that further lifts the film away from partisan politics. It’s a testimony of how freely ideas circulate in the still young state of Israel.

We Used to Sing (2021, Israel) Dir. Lidia Morozov. 32 min

Written, directed and produced by Lidia Morozov, this Israeli short is much more than meets the eye. On the surface, We used to Sing is an impressionistic portrait of the mother and grandmother of the filmmaker, a few scenes (home movies) set in an apartment close to the sea. The short accomplishes, however, with assuredness of style and substance a complicated portrait of two Russian emigrants, existentially unhappy in their surroundings and tightly bonded by blood and life experiences. Experimental and elegantly executed, the film follows the playbook of Chantal Akerman’s first-person explorations of ordinary life that paint a larger canvas of the Jewish experience.

No comments:

Post a Comment