I had the privilege in Los Angeles to become friends with two of the great documentary professors at UCLA from the 1990s to the early 2000s: Jorge Preloran (1933-2009) and Marina Goldovskaya (1941-2022). They formed several generations of filmmakers at UCLA, and taught film studies professors like me a way to approach the teaching and appreciation of the non-fiction film. If we think – paraphrasing Ken Burns – that the feature film is governed by a formula and laws of plot that make it the narrow band in the spectrum, it is the documentary that has so many glorious possibilities.

An indispensable third documentary director in my professional life has been Lourdes Portillo (b.1943), who died on April 20, at age 80, in San Francisco. The Hollywood Reporter published a succinct obituary, that captures in a few broad strokes her life and work (1).

I met Lourdes Portillo in 2014, when the Visual History Program of the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences – a mouthful - hired me to be her researcher. She was co-organizing a program of Latin American and Hispanic American filmmakers in the context of the Getty program Pacific Standard Time: Latin America in Los Angeles, to open in 2017. This resulted in a series of oral histories Lourdes conducted with Latin American and Hispanic directors, screenwriters, producers and actors over three years. These filmed interviews, beautifully produced, are available at the VHP website, and worth every minute of the viewer’s time (2). The conversations are insightful, probing the life and times of over twenty filmmakers from Mexico, Argentina, Brazil, Cuba and the U.S., including Lucrecia Martel, María Novaro, Alfonso Cuarón, Gregory Nava and Edward James Olmos. The program comprises an earlier oral history with Lourdes herself that puts the Getty project in cultural and linguistic perspectives (3).

I last talked to Lourdes in February. She knew she would not be able to continue with the project for which I was providing research. I had been her “sounding board”, she graciously said … She faced what was coming with courage, and a sense of urgency to leave her work in order.

The news of her death reminded me of La Ofrenda, a beautiful documentary that shows, as she noted, that “in Mexican culture death is accepted as a part of life and not seen as something foreign that happens to other people” (4).

A subject to explore, and one that I brought up with her preparing for the Academy conversation last year, was the role of the Catholic faith in her worldview. Lourdes’s work viewed as a whole is in tune with Pope Francis’ gospel message to take care of those at the margins.

What follows are the notes I prepared for a conversation with Lourdes in May 2022 when the Academy Museum organized a retrospective of her documentaries, “Lourdes Portillo: Una vida de directora”, to accompany the Stories of Cinema exhibition recently opened in the new museum (5).

I. The oral history she did in 2015 presents a very complete portrait of her life and work until that date. Some of the topics she discusses are invaluable to understand her career: the role of the artist in the greater society; the art of storytelling to uncover and share truths; and the esthetics of storytelling and political themes embedded in her films. Her method and style combine humor, tenacity and love, which she got from her parents, as she noted in VHP interview.

II. Documentary and truth are front and center in her film practice: “In documentary you have to be rooted in the facts, so you have to construct around the truth or what you perceive to be the truth.” “In narrative you can control almost everything whereas in documentary you can barely keep any control; you are driven by the facts.” Interestingly, the two qualities that undergird Portillo’s documentaries – love and compassion – are not usually associated with political documentaries.

III. Lourdes has a special talent for visually telling political stories, from a confined angle like that provided by families and tight communities. New Yorker critic Richard Brody wrote that her documentaries are “small-scale masterworks of intimate baroque … a controlled concentration of ordinary life, in all its extraordinariness (6). Her work needs to be seen in a continuum, intriguing blending of the personal, the political, the cultural – certainly from a point of view that is never a hammer on your face.

IV.

In 40 plus years in the filmmaking trenches, her first and last films Después del terremoto (1979) and State of Grace(2020) encapsulate her approach to cinema and most importantly, life. Lourdes’work is rooted in the artistic, cultural and political experience of Hispanics / Latinos in the US – in this order, I believe.

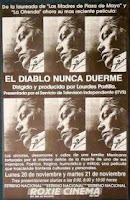

Her films of the 1980 show specific situations and groups: Después del terremoto (1979), Nicaraguans of the Somoza era living in San Francisco; La Madres (1986), an Argentine group of mothers caught in the Argentine civil war of the 1970s; La Ofrenda (1988), celebrating the dear dead in Oaxaca and San Francisco. In the 1990s – 2000s, she makes a mark with bold yet subtle documentaries experimenting with genres and film construction: The Devil Never Sleeps (1994), the portrait of her family that tells a larger social, anthropological and political picture, exploring Mexicanness (selected in 2020 for preservation in the National Film Registry by the Library of Congress as being "culturally, historically, or aesthetically significant"); Corpus: A Home Movie about Selena (1999) and its companion piece: A Conversation withAcademics about Selena (1999), an investigation of the Tejano pop star; Señorita extraviada (2001), another investigation, this time about the killings of young women in the border town of Ciudad Juárez.

Lourdes Portillo’s over seventeen films include Después del terremoto (1979), Las Madres: The Mothers of the Plaza de Mayo (1986, Academy award nomination), La Ofrenda: The Days of the Dead (1988), Columbus on Trial (1992), Mirrors of the Heart (1993), The Devil Never Sleeps (1994), Sometimes My Feet Go Numb (1997), Corpus: A Home Movie for Selena (1999), Señorita extraviada (2001), My McQueen (2004), Al Más Allá (2008), and the short animated film State of Grace (2020).

NOTES

https://www.hollywoodreporter.com/movies/movie-news/lourdes-portillo-dead-las-madres-the-mothers-of-the-plaza-de-mayo-1235878534/#recipient_hashed=12b29d8b5159fd057154e0bcb430581acfa89e6616a5e5f83cbd9e0ae424237b&recipient_salt=d798f7b01776f9545886dc9fc280537585d96e5519cf25844bcb3f8d070904ea