In festivals, very dissimilar films in form, subject and countries of origin can talk to each other in unexpected and meaningful ways. In the first four days of the 2024 Berlin Film Festival (February15 through 25) this is what happened with My Favorite Cake, an Iranian dramatic comedy entirely funded by public and private European sources, directed by Maryam Moghaddam and Behtash Saneeha; the French autobiographical pandemic-set comedy Hors du temps (Suspended Time), written and directed by Olivier Assayas; the equally autobiographic German family drama Sterben (Dying), written and directed by Matthias Glassner; and A Traveler’s Needs, a small-scale probing dissection of Korean emotional features by Hong Sangsoo, starring Isabelle Huppert as the catalyst for quiet revelations about other people’s lives.

Competing for the golden and silver bears of the Berlinale, these are above par works of imagination and with an intriguing use of film language. After years of teaching cinema history and esthetic classes in Los Angeles, it dawned on me that probably none of these films would have come out of, or been encouraged by our film schools, attuned as they are to commercial cine. The emphasis on classic narrative structures, featuring strong protagonists and antagonists, conflicts clearly laid out and solved, persuasive motivations and backstories, would not have led to the four films I note here. They have minimal plots, reveal characters primarily through dialogue and subtle acting, tend to keep motivations opaque, and avoid dramatic emphasis. Viewing these films was a gentle reminder that teaching the same subjects and discussing the same films, semester after semester, can lead to simplifications; and they can fall short of making our students true cinephiles, absorbing a wide range of cinematic experiences. Festivals are a great incentive to jump out of furrows made deep by repetition, clichés, and in the past years, flooded by ideological gobbledygook. The upcoming TCM Classic Film Festival in April, now back in the restored Egyptian theatre, is keen on discoveries and reevaluations.

I have listed these four films in order of increasing departure from standard film practices. A CSUN Cinematheque series featuring them would be an opportunity to reassess the work we are doing in forming our emerging filmmakers. It is the question at the heart of a university -run institution: How can we better expand our students'cinematic minds?

My Favorite Cake is a gentle exploration of a few days in the lonely life of a middle-class widow in present-day Tehran. It shows what happens behind the movable walls eloquently described by Hooman Majd in The Ayatollah Begs to Differ(2008). It is a private world, somewhat isolating the protagonist – an excellent Lily Farhadpoud, who also wrote the script - from the constrictions and regulations of a theocracy enforced by an omnipresent morality police. The current political context is efficiently spelled out in the dialogue and plot events, especially the death of 22-year-old Mahsa Amini in 2022, detained because her hijab was not worn right. The restrictions placed on women, material, psychological and spiritual, are the story, and the protagonist begins to assess them because at age seventy she still wants to live a meaningful life. A love story with a twist, My Favorite Cake was shot over three years, mainly with two actors, one location and some exteriors. It depicts in gentle but unequivocal terms what Jafar Panahi (Offside, Closed Curtain, Taxi), Asghar Farhadi (A Separation) and others have also been doing at great risk. Based in Tehran, the directors were not allowed to come to Berlin, and the film will not circulate in Iran. As is the political tradition of the Berlinale, the film was given a platform, and the message was not lost. Its celebration of dignity, freedom and love is universal.

In Hors du temps (Suspended Time), Olivier Assayas, a veteran of the French screen and a beloved figure in popular entertainment (Irma Vep and its recent miniseries, Personal Shopper, Clouds of Sils Maria) turns the camera to himself and the months of Covid isolation he spent in 2020 with his brother in their ancestral home. The film hinges in the personality clash between the protagonist – an exacting, obnoxious, germophobe film director, Assayas’ alter ego (Vincent Macaigne) – and his equally insufferable music critic brother, who flaunts his annoyance with precautions, masks and unruly germs. The fighting is purely verbal, a linguistic staccato that skewers the gamut of responses to the pandemic. (Added fun is to place oneself in one of the two camps sharply delineated). There is no American-style conflict in this slice of French life under the coronavirus regime; the comedy is carried on by long-winded conversations - Eric Rohmer style – with verve and witty cultural references. Key to the comedy’s success is carried its location – the proverbial, civilize French countryside – and the dialogue, including a first-person narrator that pokes fun at himself, with dollops of nostalgia for a childhood fondly remembered. Nothing earth-shattering happens in the film, and the total halt to these busy lives allows for both a reckoning and a pleasant happy ending.

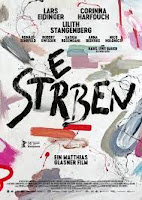

Sterben hinges on dying, literally and figuratively, both as the physical death of one’s parents and its aftermath, and the nature of creation and the toll it takes on the artist. It is divided in chapters, offering not only the point of view of key characters, but also explicit comments on life. The last one is tellingly, “Love”. The film proposes the concept of “kitsch” to describe how an elderly couple has lived by the time Alzheimer’s and cancer get them, and how their two emotionally distant children grope for a meaning to their lives. “Kitsch happens when our emotions and feelings do not match with reality”, one of them notes. Sterben works out its plot through this insight, not so much about what happens to the characters, but the way they reach awareness in their life journey. The siblings’ insights are revealed in two key moments, superbly staged: the last conversation between mother and son - a reckoning with echoes of Ingmar Bergman - and the daughter’s physical reaction to the world of high culture her brother belongs to, at the fabled Berlin Philharmonic theater. The siblings also represent the clash between chaos and order, the belief in radical autonomy and the realization that there is a price to pay. Composed specifically for this work, Sterben is a musical piece that, through several important transformations, captures the meaning of the film in its moving climax. Sterben is about the tragicomedy of life, pared to its essentials, by virtue of its sharp writing, mise-en-scène and nuanced performances by veteran Lars Leininger, Corinna Harfouch and Lilith Stangenberg. Sterben is not interested in the three-act structure and other workings of the Hollywood screenplay. It is absorbing because we can recognize the human experience in the foibles of these characters dealing with the curveballs of life.

Stylistically, the most audacious of the four films is A Traveler’s Needs: it is drained almost to the bone of dramatic action. During a few hours one day in Seoul, Iris, a French woman played by Isabelle Huppert, teaches the same French language lesson – in English – to a young adult and a married couple. She has a heterodox method – perhaps she is an improvised instructor, lacking pedagogy and textbooks. The film jumps in media res into the two conversations. The scenes have the same set up – long takes in parks. Twenty minutes into the film, the same blocking of the scenes and lines of dialogue lovingly showcase the politeness and emotional restrain that are Korean clichés. However, these two conversation perform an intriguing function: they beg the question, who is this middle-aged frazzled woman and what is she doing in Korea? The third conversation is with between Iris and her host, a young poet of little financial means who has offered to share his modest lodging. The unexpected visit of his politely overbearing mother flashes out questions that loom large, regarding this polished foreigner who may have ulterior motives. The film concludes without any climax or explanation, with allusions to poetry and beauty hanging in the air. A Traveler’s Needs relies on the stellar, understated yet nuanced performance of Huppert (in a striking green and orange outfit), and the other four actors. Less is more and the unrevealed mystery of this traveler and her needs may not be far our experience in real life. We are always intrigued by other people’s Rosebuds.

Viewing these films, another thought dawned on me: if Gustave Flaubert had been our contemporary, he would be writing movies like these, organizing a world around characters we can understand but cannot quite figure out; characters that refuse to yield us their mystery, since "the heart has its reasons which reason knows nothing about", as Blaise Pascal noted in his Pensées. We are far away from the Greeks and Shakespeare. It is Madame Bovary territory.

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

No comments:

Post a Comment